Charles Thomas

Aspiring Theoretical Physicist

DNA Sequencing & Graph Theory

by Charles Thomas

DNA sequencing has been a technological revolution. It has many application from medicine to forensics. It also has some clever mathematics behind. In this article I aim to explore the basics of the application of graph theory to DNA sequencing.

What is DNA sequencing?

DNA is the building block of life. It consists of two chains of molecules arranged in a double helix. Each link in the chain is one of 4 molecules called nucleotides. They are cytosine (C), guanine (G), adenine (A) or thymine (T).

DNA sequencing is the process of trying to work out what order these modules appear in the chain.

Since these chains are very long it is necessary to split the chain up into smaller fragments. We can then sequence the fragments and put them back together. This becomes a problem when we don’t know what order the fragments come in. Luckily, we can apply graph theory to solve this.

Graph Theory: A primer

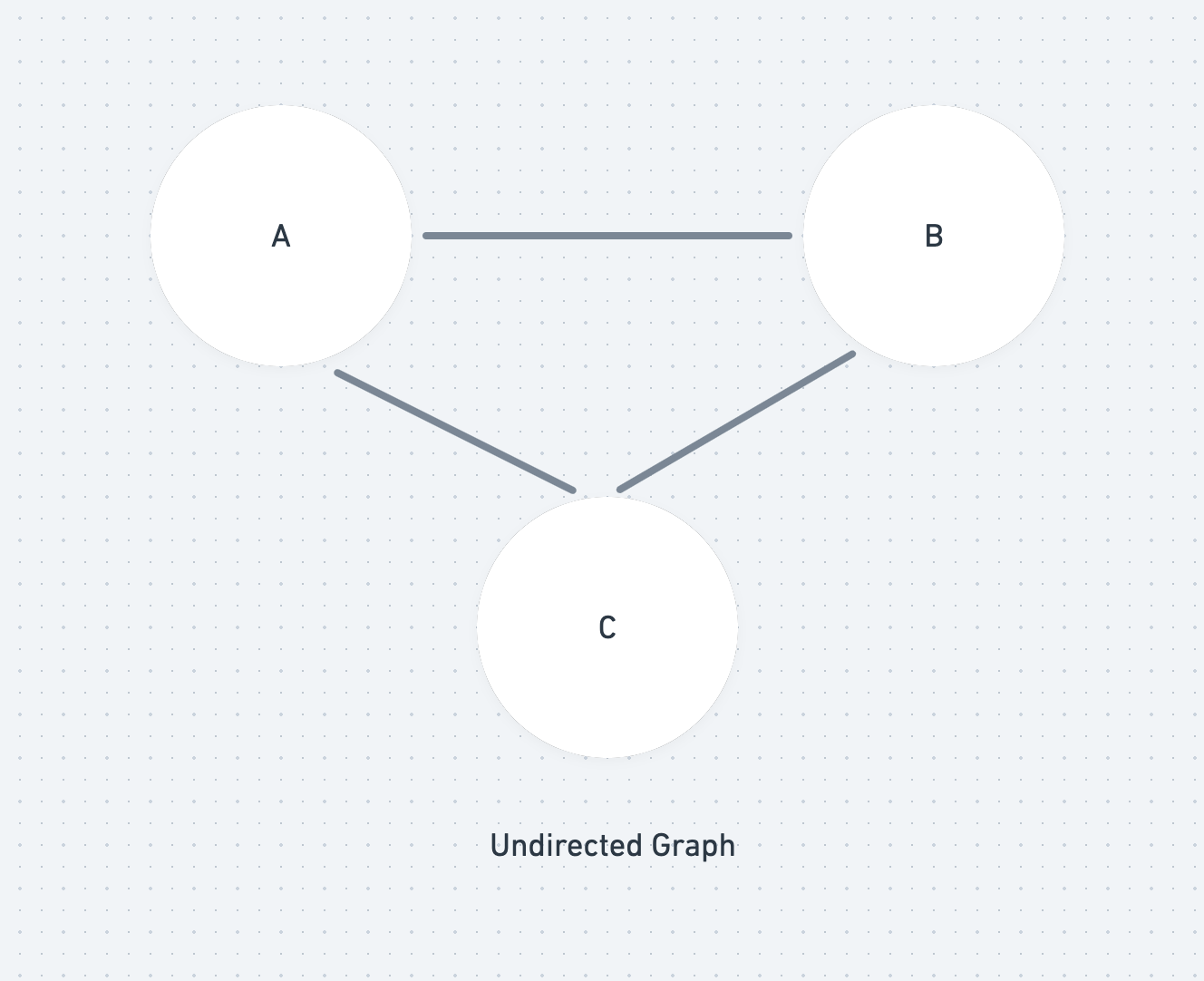

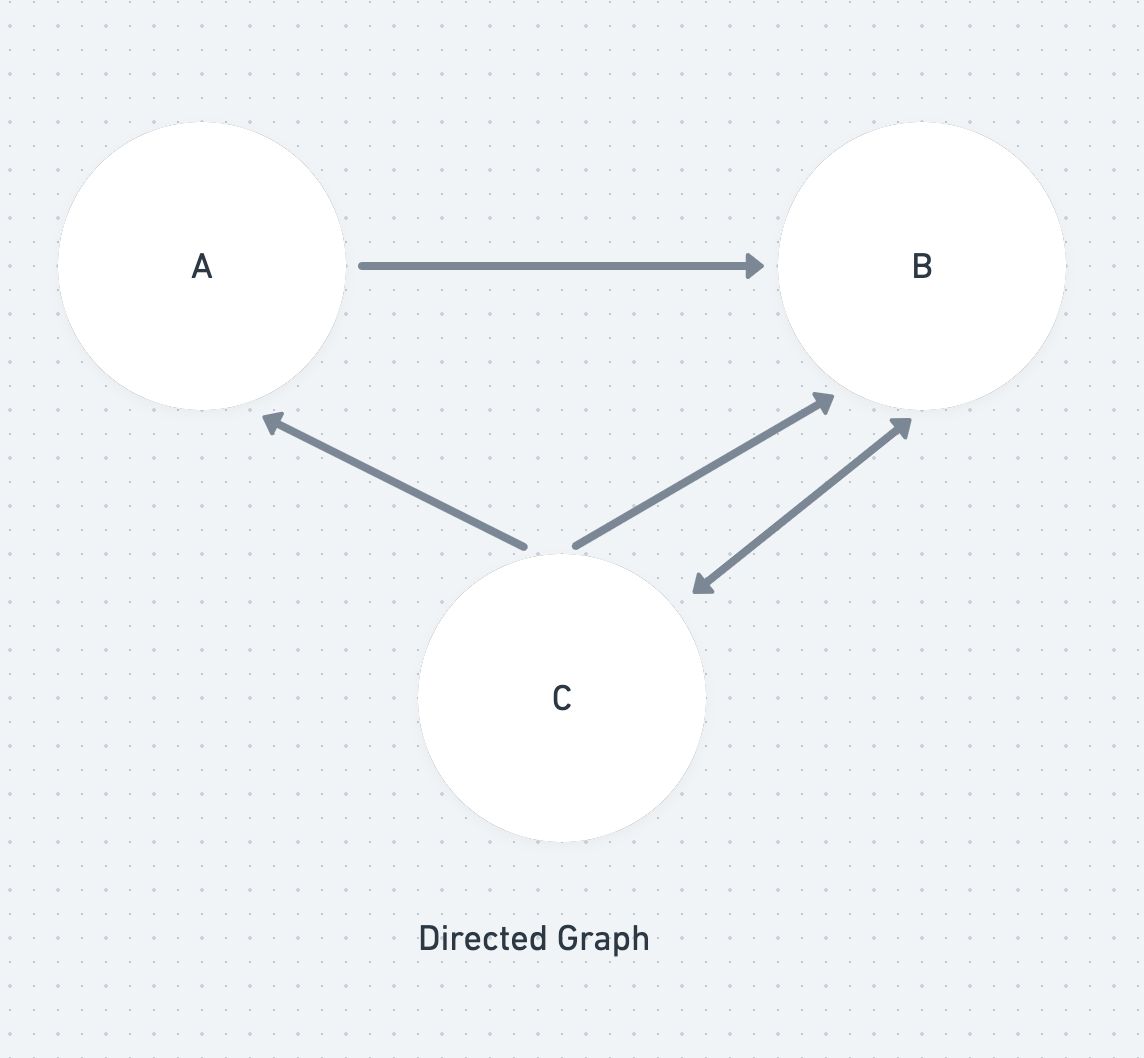

A graph is made up of two things: a collections of points (nodes) and a collection of lines (edges) that join together two of the points. In a directed graph, the lines (edges) are arrows that only go one way.

A walk is a collection of edges that join vertices. If no edges are repeated then the walk is known as a trail. If no edges and vertices are repeated then it is known as a path.

A Hamiltonian path is a path is one that visits every node in a graph once. An Eulerian path is a path that visits every edge once.

Applying Graph Theory - Hamiltonian path

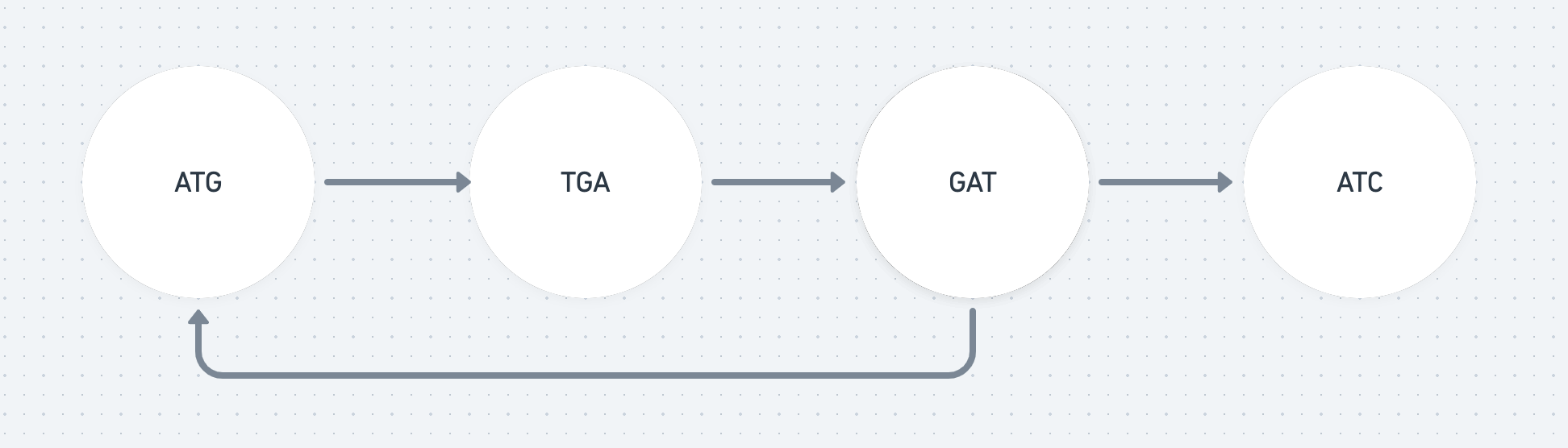

When we have our fragments of DNA they can overlap. We can use this to help stitch them together.

Let’s assume our fragments (often called mers) are 3 molecules long (3-mer). For example, we might have the fragments: ATG, TGC, GTC. Let’s also assume they overlap by two molecules. This means the fragment ATG must be followed by a fragment beginning with TG e.g. TGC.

We can create a graph where every node is a fragment. And there is an edge going from a node to another if they overlap by two letters. So the node ATG would have an edge connecting it to TGC.

If we find a path that visits every node once (a Hamiltonian path) we have a found an ordering of the fragment that makes up the whole DNA sequence.

Sadly, finding a Hamiltonian path isn’t easy (it is classed as an NP-Complete problem).

Applying Graph Theory - Eulerian path

Luckily, there is another way of phrasing this problem.

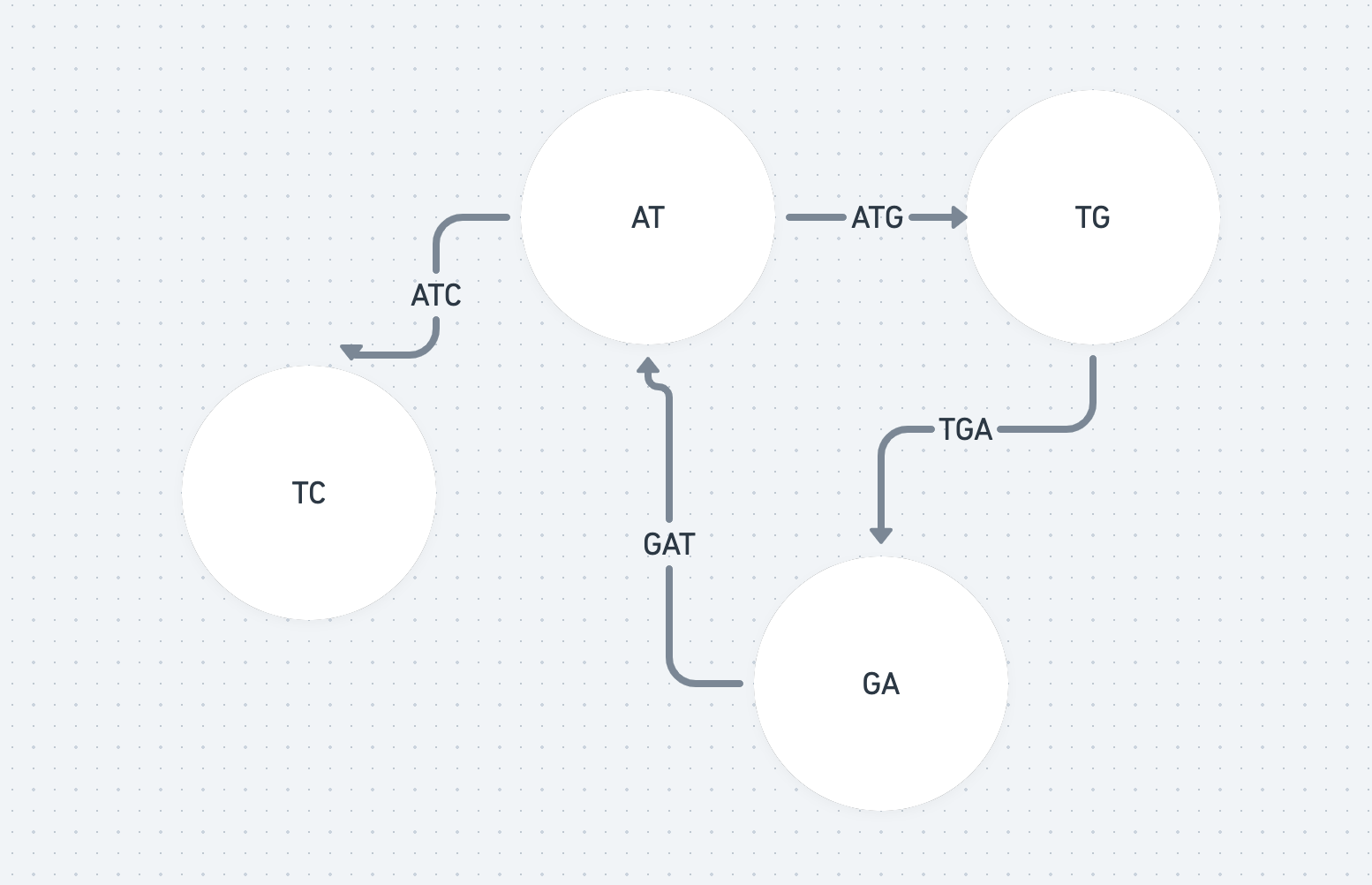

For every fragment, let’s split it into the first two characters and last two characters and make each of these nodes. So CTG becomes the nodes CT and TG.

Now, we can represent every fragment by an edge joining the two nodes that make it up. So an edge the between CT and TG represents the fragment CTG. (This is a case of a De Bruijn graph - see [3] for more details)

If we can find an path (a set of edges) that visits every edge once (an Eulerian path) we’ll have found the ordering of our fragments.

Finding a Eulerian path - Hierholzer’s algorithm

Thankfully, finding a Eulerian path is much easier than finding a Hamiltonian one. There is an algorithm that runs in linear time called Hierholzer’s algorithm that we can use.

The algorithm works by picking a starting node. Then randomly following edges until it returns to the starting node (this is a cycle - a path that starts and ends at the same place).

If there any remaining unvisited edges start with a node that is connected to one of them and repeat the process. Then merge the two cycles. For example, if I had a cycles A, B, C, A and B, D, E B merging them would produce A, B, D, E, B, C, A.

You repeat this until there are no unvisited edges.

Note: For this to work we have to know an Eulerian path exists. There is an easy way to check this. Call the number of edges going into a node the in-degree and the number of edges leaving a node the out-degree. An Eulerian path exists if there is a most of node where the in degree and out degree differ by 1.

Conclusion

Sadly, in real life there are some other problem that make this process harder. One example is if a fragment occurs multiple times in a sequence (see [6] for more details). However, I hope this post gave you an insight into how graph theory can be applied to genetics.

Notes

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shotgun_sequencing

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/De_novo_sequence_assemblers

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/De_Bruijn_graph

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5531759/

- https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/proof-hamiltonian-path-np-complete/

- https://slaystudy.com/hierholzers-algorithm/